It’s a miracle-worker for road crews trying to keep highways clear of snow and ice, but once the cold breaks it can leave your landscape withered.

Road salt cuts through snow and ice like magic, leaving dry and safe roadways when everything else is covered in white. Unfortunately for your lawn and landscape, the salt doesn’t magically disappear. It soaks into your soil and gets absorbed by your turf and your favorite plants. Once winter breaks, it becomes a real problem, especially in the coldest, iciest areas.

“Salt is a pretty good weed killer in itself,” says Bill Craig, ag services director for Marshall and Pennington counties with the University of Minnesota Extension.

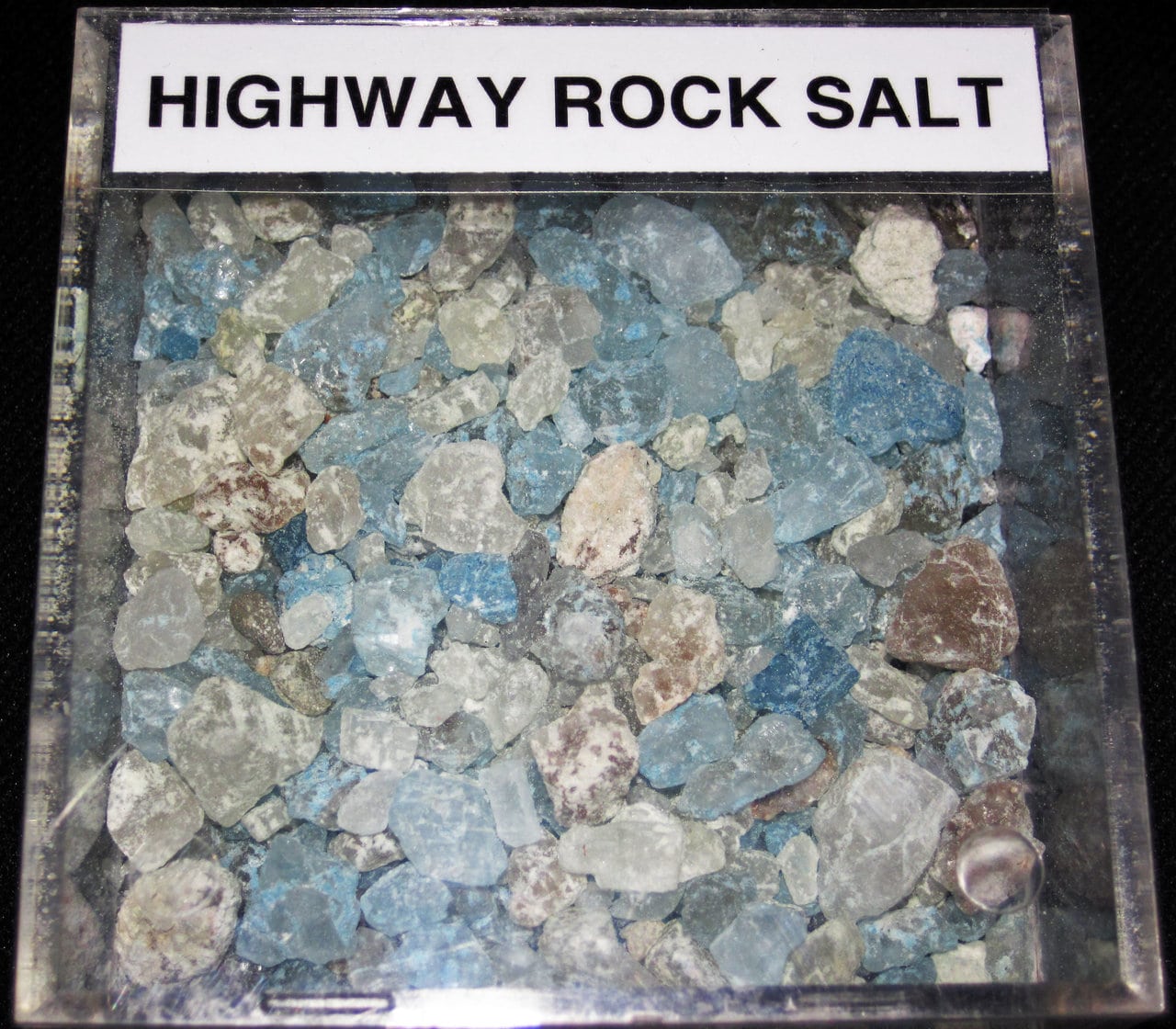

Craig says Minnesota is widely known for its use of road salt. Also known as rock salt, sodium chloride, and halite, road salt is the most widely used de-icer due to its relatively cheap cost, and the fact that it works. In the Twin Cities alone, 365,000 tons of salt are dumped on the roads in winter, polluting lakes and other waterways with its runoff.

While the state is studying ways to cut its use by applying it more smartly, salt appears to be in the winter forecast for landscapes in Minnesota and every other state where icy roads are common.

When moisture follows, that salt runs off into your yard, affecting plant growth and maybe killing the plants it reaches.

Homeowners also tend to find salt damage along the edges of concrete surfaces like driveways and sidewalks, Craig says, even when they’re applying the salt themselves.

Want to avoid salting the earth in your own front yard? Here’s what you need to know.

A Big Salty Problem

Salt is an important part of keeping roads open while snow covers everything else, but the amount of salt spread on land surfaces around the United States is astounding.

An estimated 20 million tons of salt is scattered on the country’s roadways annually, according to the Earth Institute at Columbia University.

That’s about 123 pounds or every single person. And that doesn’t take into account what’s spread on sidewalks or driveways by homeowners.

Chemically, it’s a lot like the table salt you put on your eggs in the morning, that is, sodium chloride. Those molecules separate once the salt is dissolved in water creating a solution of chloride ions and sodium ions, which interfere with the water’s ability to bond together and form ice.

It’s called freezing point depression, and while that part has been long understood, the lasting effects of that salt on the land have not.

Columbia cites studies showing that more than a third of contiguous U.S. has increased in salinity in recent decades. One study in New York found nearly half of 125 sampled wells in Dutchess County had sodium concentrations exceeding EPA guidelines.

The effect of that salt spreads in all directions. It not only contaminates soil and harms plants sprayed by passing cars, it affects animal, insect and aquatic life too, as well as drinking water sources.

How Salt Hurts Plants

So what does this artificial salinization mean for the plants in your yard? Nothing good.

“Most plants can’t tolerate a lot of salt,” Craig says.

The Iowa State University Cooperative Extension explains why.

When too much salt accumulates in the soil, most typically the areas closest to the road, it can reach toxic levels that keep plants from absorbing enough water, no matter how wet the soil is.

When salty water is sprayed from passing cars onto your shrubs or trees, it dehydrates the plant tissue.

Your favorite lawn feature isn’t immune. Landscape plants such as trees, shrubs, perennials and turfgrass are all susceptible to salt damage, and spray from passing vehicles is particularly harmful for evergreens.

What Salt Damage Looks Like

Grass

What many homeowners find is thin or dead grass along their driveways, says Craig. Over the winter, they’ve been adding salt to keep the driveway free of ice.

But as it slowly runs off, the de-icer builds up in the soil next to the concrete and kills the grass growing there.

Trees

- Deciduous trees and shrubs will see stunted growth, scorching around leaf edges, early fall coloration and twig dieback.

- Evergreen needles will yellow or brown and twigs will dieback as well.

The Purdue University Extension explains just how that damage happens.

When salt dissolves in water and the sodium and chloride ions separate. When a plant absorbs this water, those ions replace other nutrients in the soil the plant needs.

Chunks of rock salt can also absorb water that would otherwise go to the plants’ roots, dehydrating them, changing their physiology and causing additional stress.

Is It Salt Damage?

Salt damage can be difficult to spot and after a long snowy winter, it may be hard to tell if that’s really what’s giving you problems.

Damage from de-icers varies. Factors including plant type, salt type, fresh water availability, runoff and more all play a part, says the University of Massachusetts Center for Food, Agriculture and the Environment.

Salts applied in late winter generally do more damage. That’s because it leaves less time for the salt to wash through the soil before new growth starts back up in spring.

The volume of fresh water applied to the soil also makes an impact, and rainfall can wash leaves clean of salt spray or residue.

To really find out what’s going on get a soil sample, says Craig. The results will show the parts per million of salt in your soil so you can figure out how to fix it-or whether you even need to.

Common Salt Damage Symptoms

For your plants, UMass lists some common symptoms of too much exposure to de-icers:

- Damage mostly on the side of the plant facing the road.

- Browning or discoloration of needles beginning at tips.

- Bud damage or death.

- Twig and stem dieback.

- Delayed bud break.

- Reduced or distorted leaf or stem growth.

- Wilting during hot, dry conditions.

- Reduced plant vigor.

- Flower and fruit development delayed and/or smaller than normal.

- Needle tip burn and marginal leaf burn.

- Discolored foliage.

- Nutrient deficiencies.

- Early leaf drop or fall color.

Preventing Salt Injury

The first thing you can do to mitigate salt damage to plants is to stop using salt, or at least reduce how much you’re using.

De-icing salt should be kept to high-risk areas, says a detailed guide from Dane County, Wisc.

It’s best for highways, intersections, hills, steps and major walkways and its application should be limited in noncritical areas.

And whether you’re using pure sodium chloride or not, you can dilute it with another abrasive material such as sand or kitty litter. It won’t keep water from freezing the way salt will, but its abrasiveness helps tires or boots gain traction on the slick surface.

Dane County gives an example of one pound of salt diluted with 50 pounds of sand, which it says is an effective abrasive compound, especially on walkways.

Wait until after all the snow has been plowed or shoveled if using a de-icer, but early applications of small amounts of salt can go a long way in preventing ice from bonding to pavement.

Keep an eye on your water runoff, too, says Craig. If water runs onto plants you want to protect from an area that gets salted during the winter, he says, it’s time to reroute it.

“Find a way to divert that water to keep the salt away,” he says.

Salt-Damage Prevention Tips

The Dane County guide gives other tips, too:

- Don’t apply salt in late winter.

- Plant trees and shrubs on berms if in areas susceptible to salt application.

- Avoid shoveling salt-laden snow over the root zones of susceptible plants.

- During a warm spell in winter, rinse plants off to remove residual salt.

- Water heavily in early spring to flush salt from your plant roots.

- Use barriers like gutters to move salt runoff away from plants.

There’s one more option to prevent salt damage to your plants, especially if you have susceptible plants very near a busy roadway: physical barriers.

Purdue says to erect barriers of plastic fencing, burlap or snow fencing to protect sensitive plants and minimize their contact with salt.

De-icing Alternatives

Traditional salt, in the form of sodium chloride, isn’t the only option.

If a homeowner is trying to prevent salt damage, using a substitute is Craig’s recommendation.

Salt substitutes do a pretty good job, he says, and a substitute is about the only option homeowners have.

The Purdue University Cooperative Extension breaks down several other de-icers by their effect on both road ice and plants.

- Sodium Chloride: works as low as 16 degrees and softens ice at lower temperatures. It’s inexpensive and effective, but damaging to roadside plants via sodium and chloride ion toxicity.

- Potassium Chloride: works as low as 12 degrees. Doesn’t harm plants but more expensive than sodium chloride

- Magnesium Chloride: works down to 5 degrees, and won’t harm vegetation at suggested usage rates but contains more chloride than other products. More expensive than sodium chloride.

- Calcium Chloride: melts ice at temperatures to -25, and effective to -59. Won’t harm vegetation if used properly, but more expensive than sodium chloride.

- Calcium Magnesium Acetate (CMA): will work below 0 degrees. It’s low toxicity and biodegradable, even adding nutrients plants need in calcium and magnesium but is the most expensive option.

Salt-Tolerant Plants

Sound like a lot of work? Don’t think you’ll be able to protect those sensitive plants this winter?

Just replace them with ones that like — or at least tolerate — salt.

“Look for plants that have the most salt tolerance,” Craig says.

Plants growing in the salty soil will help rehabilitate it, he explains, by continually recycling nutrients and keep the soil from going dormant and breaking down.

In Minnesota, where farmers struggle naturally salty soil in the form of high calcium, Craig says they’re looking for salt-tolerant plants to grow and get the soil in better condition.

Dane County lists more than 100 salt-tolerant plants in its guide that have either moderate or high levels of tolerance to salt.

There are plenty to choose from, like high-tolerance deciduous trees from the Acer and Quercus families like Hedge Maple and Norway Maple, White Oak, English Oak, Northern Red Oak, and Evergreen species from the Pinus family like Jack pine and Ponderosa pine, and even vines, groundcovers and ornamental grasses.

There also are some salt-resistant turfgrasses to consider for your lawn.

On the other side of the spectrum are salt-sensitive plants you need to avoid.

The University of Massachusetts lays out a few in their guide, including dogwoods, eastern white pine and serviceberry.

Repairing Rock Salt Damage

Trying to figure out how to bring your plants back from the salty brink?

The bad news is there isn’t much to do about a plant that’s been severely damaged by salt. The good news is you can always replace it.

If Your Plant Is Salvageable

- Start irrigating the area, says Craig. Watering will help wash the salt further down into the soil, diluting it in the process.

- Add some peat or topsoil to areas of turf affected by salt and reseed areas you’ve lost.

Replacing the Plant

But if those roadside bushes are toast and you do replace them, either choose a salt tolerant plant or install some drainage or other improvements to help protect it from salt in the future.

And replacing larger landscape plants is a good chance to work on the soil too.

“If I was pulling up my shrubs, I would replace the soil too,” Craig says. “If you have water running over that area, find a way to divert that water and keep the salt away.”